This is far too big of a topic to cover in just one blog, however, I’d like to talk about a few things related to your on-stage persona.

What you say and do and how you act in certain situations define your character. Every single action you take paints a clear picture of this persona. From the audiences point of view, they’ve never met you before, so you need to work to show them who you are. You’re more than just a magician; you’re a person with a life, hobbies, strengths and weaknesses, stories, fears, jokes, tragedies and personal victories and so so much more. The audience doesn’t need every single detail. But it’s nice over the course of your show to allow them to clearly see who you are. You can be way more than just some guy doing tricks. How do you do this?

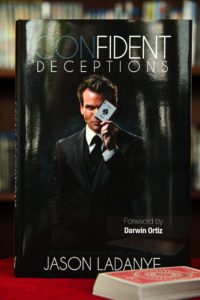

First, you need to really understand who you are on stage. My character is a silky smooth con man and cardshark, completely ego driven, full of himself, cocky, arrogant, a ladies man, a liar, cheat, a thief, nothing’s ever my fault, I’m a bit of an asshole… in other words, I play myself on stage. (In all seriousness, I’m actually hardly any of these. I’m a bit of an introvert and I stole stuff years ago but that wasn’t my fault.)

You may be something else: a spiritual person that connects with the universe, a bumbling idiot that fumbles with all the props yet that magic still happens, someone that’s very sure of himself but can’t actually do anything (Jibrizy?) You can be dead serious and mysterious–selling that everything you do is 100% real. Or you can be a comedy magician that gets great laughs and hints that the magic is just tricks. Are you someone that’s in control of your skill set, or are you sharing with the audience something you only have a vague understanding of? There are endless opportunities for what type of character you want to play on stage. How do you let the audience know this character once you have it down?

During your show, you need to be sure that all of your patter, your movements, your script, your jokes, your props, your attire, and everything else is consistent with your character. I wear a super expensive suit and drink fine single malt scotch on stage. If you’re bumbling idiot, you may not convey that to the audience with a perfectly tailored suit. You could wear one of those tuxes from Dumb and Dumber to show you know enough to dress up, but your taste in clothes is a bit off… just like your magic. This character only knows a little bit about magic, and that’s why everything goes wrong.

Let’s look at a basic effect and see how different characters may perform it. The performer has two cards of different values, a high card and a low card. The cards are mixed and the performer can tell which is which–a simple Two-Card Monte plot.

My character would say, “Last time I was at the Bellagio, I stole a few cards during a game of blackjack. Hey, I prefer to play the cards of my choosing when my money is on the line. Anyway, with these cards, we’re going to play the classic con game Three-card Monte. But I’m actually so good I can still win the game using only two cards. Your odds of winning are now 50%! How could you NOT play?” (The two cards I’d use would be actual Bellagio cards pulled from an expensive Italian leather wallet.) Right away the audience gets lots of information. Compare this to: “Here’s a trick with two cards.” The performer is missing out on a chance to develop the character.

The bumbling idiot may say, “Can you believe on the way to this show I lost my life savings playing three-card Monte? Anyway, I want to play Monte with you right now. I wanna to see if I can win my eleven bucks back… Aww, I already lost one of the cards. Can we try two-card Monte instead?” He then pulls two folded up mangled cards from his pockets dropping some spare change and a few random funny items and on the floor. The two cards don’t even have matching backs. Again, the audience gains so much information about the character here. (Note my character said, “We’re going to play…” and this character asked, “Can we play?” One’s confident and in charge, the other is not.)

The mentalist that’s unsure of his powers may say, “People often ask if I can use my abilities to win money. Well honestly I have thought about it. However, I don’t want to take peoples money. But I am curious. Let’s try an experiment with two tarot cards.” The spectator is instructed to place a small crystal ball on either of the two tarot cards while the performer’s back is turned. The performer can sense which of the two cards the ball is on. There’s no winner or loser.

If I play the game, I win every time. If the idiot plays the game he can lose every time. The mentalist isn’t playing against anyone, but he’s able to know which card is which while his back is turned. Look how we can take one simple effect, and depending on your character, come up with completely different versions. These are all hypothetical versions of course, but you can think about the material you do and your character and make sure that everything is consistent.